Primal cuts are the big chunks that make for easier handling of whole carcasses after the animals has been slaughtered and hung. Well known and understood in the realms of professional food service, chefs, butchers and meat counters, primals are not as popular or well-understood by most consumers because they are not readily available.

Primal cuts are the big chunks that make for easier handling of whole carcasses after the animals has been slaughtered and hung. Well known and understood in the realms of professional food service, chefs, butchers and meat counters, primals are not as popular or well-understood by most consumers because they are not readily available. But as the farm-to-table, sustainable, localvore, humane, organic, pastured livestock movement gets a foot-hold, home meat purchasers are going to start seeing a lot more of these types of cuts previously only known to the world of professional meat. Let me explain.....

First, in raising livestock the reality is that not all animals are going to produce the premium cuts that so many customers are accustomed to thanks to industrial agriculture. Many breeds of meat animals have been bred to put on as much muscle as possible in a short amount of time with minimal inputs. Often, this means grain-fed. Think of those plump, well-marbled lamb chops with their tasty medallions of loin the size of a lid on a Mason jar. And it seems that all the leg-of-lamb recipes on the Food Network or any other popular media outlet begin with 5-8 pound piece of meat.

First, in raising livestock the reality is that not all animals are going to produce the premium cuts that so many customers are accustomed to thanks to industrial agriculture. Many breeds of meat animals have been bred to put on as much muscle as possible in a short amount of time with minimal inputs. Often, this means grain-fed. Think of those plump, well-marbled lamb chops with their tasty medallions of loin the size of a lid on a Mason jar. And it seems that all the leg-of-lamb recipes on the Food Network or any other popular media outlet begin with 5-8 pound piece of meat.But in using lambs as an example in comparison to goats, it's apples and oranges--or should I say caprines and ovines. First, there are two distinctly different body types for goats--dairy and meat--similar to cattle. One has been bred to put as much energy as possible into milk production resulting in a thinner, leaner framed animal. Animals bred to produce meat have heavier, well-muscled bodies and once the skin comes off, this difference becomes even more evident.

I've always been amazed by people who think that there is a hard and fast line between production animals and their ultimate destination--milk animals are not used for meat, meat animals are never milked and the two are never bred to each other. But many milk producers (especially in the goat world) breed their females to meat-style males in order to produce more marketable male offspring.

However, in doing so, the phenotype of these offspring don't always exhibit strong meat-type traits and thus must be harvested at a smaller weight in order to produce a marketable (and profitable) product. To allow young male goats with more dairy characteristics to grow larger would require more inputs and time, but still may result in larger bones with minimal muscling and no one wants more bone than meat on their dinner plate. Instead, these animals are harvested at a younger age while still plump from the fattier diet that includes their mothers' rich milk with bones proportional to their meat ratio.

Again the question is raised, "Why primal cuts?" This time it boils down to economics. As red meat sold at farmers markets, it MUST be processed under USDA inspection. You'll notice not just the blue stamp on the meat, but the little round circle on the label with the processing facility's identification number. Most USDA processors charge a flat fee for killing, cleaning, hanging, cutting and packaging a small ruminant (goat, lamb or veal). The smaller the animal equals the larger cost per pound for processing. When smaller animals such as milk-fed kid and lamb (usually 50 pounds and less live weight) are processed, it makes more economical sense to cut into primals otherwise the cost per pound would have to be significantly more. And I can guarantee that no one wants to pay a premium price for a pathetic cut of meat. (yes, this is the voice of experience)

Part of being a good farmer and direct marketer is knowing when to harvest an animal that is going to satisfy both the customer and the seller.

This is why the latest batch of goats to be harvested have been cut as primals. They were milk-fed kid goats from dairy/meat crosses that just weren't going to yield well at the minimum size required for individual cuts. As my customers know, one of the big reasons I raise meat is due to my former life in the professional food realm. I want to produce delicious and organically raised meats, most of which I have found difficult to obtain due to our industrialized food system. That includes naturally-browsed goat meat, milk-fed kid, humanely-raised rose veal and pastured poultry.

So, what are the primal cuts available and how can they be used?

Basically, an entire goat is cut into six large pieces--three from each side. Here they are with an explanation of what they normally would be broken down into on a larger carcass and tips for how you can either break them down yourself or cook them whole.

Forequarter--this is comprised of the whole shoulder, foreshank, neck and breast. Lots of great connective tissue, too, that makes for rich stews and curries. The various cuts can be separated at the joints using a only sharp knife. Individual cuts can be roasted, braised or grilled. As there is much less fat on goats than on lamb, beef, pork or chicken, if you smoke goat it is best to wrap in foil so it does not dry out. This primal cut is the heaviest, typically weighing 4-5 pounds.

Rack--this is what I consider the best of the best. Cuts from this primal include rib chops, loin chops or without the bone, the entire loin can be fileted off the bone--a real luxury! There are also ribs and belly. One of my all-time favorite things to do with this cut is put it meat side up on a large baking sheet, sprinkle with a mixture of bread crumbs, fresh herbs (especially rosemary), olive oil, a flavorful hard, dry grated cheese (don't you dare use fake Parmesan out of a cardboard can), fresh black pepper and large grain sea salt and bake for 20-30 minutes in an oven preheated to 450 degrees. You can do this on an outdoor grill or even better, in a wood-fired oven. Fair warning, if you want to cut your own chops, you are going to need a saw or a heavy cleaver. This primal cut is the smallest, typically weighing 2 3/4 to 3 1/4 pounds.

Leg--the entire rear leg is comprised of the chump, leg and shank. While most people like to roast up one of these bad boys on a rotisserie, just as easy and delicious is cutting the meat off the bone in large cubes and making kabobs. Similar to the rack, the leg can also be roasted until the internal temperature at the thickest part of the leg reads 150-155 degrees F with a meat thermometer. This primal cut typically weights 3 1/2 to 4 1/4 pounds.

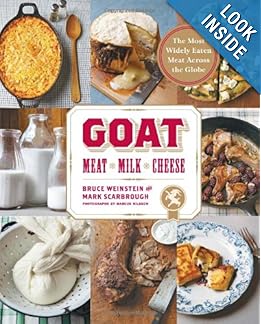

And if you're still left wondering how on earth to cook goat meat, I would suggest Bruce Weinstein's book, GOAT: Meat, Milk, Cheese which as many wonderful recipes, including my favorite Goat Chops with Blackberries.